Celebrating the Casio QV-10 – the world’s first consumer digital camera with built-in LCD

‘What to do today?’ was one of my dad’s daily musings, and while pondering the same thing myself, I remembered that I’ve got a vintage digicam that I wanted to re-visit and explore. So this item is dedicated to the Casio QV-10, which nearly 30 years ago heralded a radical change in the way consumers would enjoy photography in the future.

It’s the 1990s and mainstream film photography is reaching its zenith, with many high quality 35mm and medium format film cameras available that were hand-made and of exquisite complexity. I ‘cut my teeth’ on Minolta’s film camera range, mainly because I’d spotted a second-hand 50mm Minolta macro lens on sale in a local camera shop, so I bought a used Minolta X-700 SLR camera body to go with it, to support my electronics project publishing job.

After getting my hands on this quality lens, I learned about photography basics including aperture (f-stops n’ things), shutter speeds and ISO settings. I increased my knowledge on a need-to-know basis, as I embraced exposure values (EV), a macro ring flash, lens filters and extension tubes as well. Using this esoteric equipment was a highly rewarding experience and, with the Internet starting to take off, my resulting close-up photography enabled me to produce the world’s first website dedicated to explaining the techniques of electronics soldering.

In 1996 the Basic Soldering Guide was born! It can still be seen today (click through to the Photo Gallery) at

https://web.archive.org/web/19990225151816/http://www.epemag.wimborne.co.uk/solderfaq.htm

Film cameras had their downside of course. Apart from being cumbersome and heavy, film obviously needed processing, something we entrusted to the local photolab. This was disruptive and time-consuming especially as I had a busy writing and publishing schedule to adhere to, so I was excited when in the mid 1990s the prospect of using instant new ‘digital’ photography started to surface.

Kodak was first to market a digital camera which, due to its high cost and complexity, was aimed fairly and squarely at professional photographers and studios. The Kodak DCS100 comprised an electronic CCD sensor grafted onto an SLR film camera body, so images were captured up-front the traditional way but were written to an internal digital memory instead of a film plane. However, the LCD technology that displayed images on a screen, had yet to materialise. An interesting history of the Kodak Digital Camera System is on Wikipedia here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kodak_DCS

Casio QV-10 - the first digicam with LCD [click to see]In Britain, the idea of digital photography was in its infancy when Casio launched the world’s first consumer digicam with an LCD, the QV-10, in 1995. It would prove to be a seminal milestone in photography as it now enabled users to view their snapshots instantly (nearly, anyway) on the camera’s built-in 1.8” Active Matrix TFT colour screen.

Casio QV-10 - the first digicam with LCD [click to see]In Britain, the idea of digital photography was in its infancy when Casio launched the world’s first consumer digicam with an LCD, the QV-10, in 1995. It would prove to be a seminal milestone in photography as it now enabled users to view their snapshots instantly (nearly, anyway) on the camera’s built-in 1.8” Active Matrix TFT colour screen.

The LCD also doubled as a digital viewfinder, something that had never been possible before. The camera’s specification might seem archaic now, but it was cutting edge in its time and the Casio QV-10 held great appeal for two other emerging 1990s mainstream technologies: the exciting worlds of personal computing and desktop publishing. For the first time, digital photography became easy and affordable - “Now it doesn't take a PhD to use a digital camera” as Casio said of the QV digital camera.

The LCD viewfinder was a world first in this market [click to see]As ‘flash’ removable media had yet to arrive on the scene (never mind USB), the camera hosted its own 16MB internal memory (though the early spec only quotes 2MB), and it took 6-7 seconds for each image to be written to memory. Images could only be downloaded using a dedicated serial lead with a Windows PC or Macintosh. Using Casio’s Connection Kit, you could also copy images from your PC back onto the camera again, which might have been handy for giving presentations or slideshows.

The LCD viewfinder was a world first in this market [click to see]As ‘flash’ removable media had yet to arrive on the scene (never mind USB), the camera hosted its own 16MB internal memory (though the early spec only quotes 2MB), and it took 6-7 seconds for each image to be written to memory. Images could only be downloaded using a dedicated serial lead with a Windows PC or Macintosh. Using Casio’s Connection Kit, you could also copy images from your PC back onto the camera again, which might have been handy for giving presentations or slideshows.

Trendy estate agents (realtors) soon embraced the flashy idea of using the QV-10 digital camera to photograph their client’s houses. It all looked very exciting and high tech. One problem was that image resolution was low (320 x 240 pixels – quarter VGA) and houses and their interiors were often quite blurry.

No doubt the silent 'click' of the Casio's shutter button contrasted heavily with the click and whirr of a film SLR, and users of the time would have been held in awe of this new digital image capture technology.

The DC power supply lead sprouted inconveniently from the top [click to see]A Video Out jack and RCA lead enabled viewing on a TV screen, video ‘still’ thermal printer or a video tape deck, a concept that was a great novelty at the time. Casio’s all-plastic photographic prodigy weighed in at just 170 grammes and it used four AA batteries or a 6V mains adaptor (centre negative!), though the DC lead stuck out of the top and got in the way.

The DC power supply lead sprouted inconveniently from the top [click to see]A Video Out jack and RCA lead enabled viewing on a TV screen, video ‘still’ thermal printer or a video tape deck, a concept that was a great novelty at the time. Casio’s all-plastic photographic prodigy weighed in at just 170 grammes and it used four AA batteries or a 6V mains adaptor (centre negative!), though the DC lead stuck out of the top and got in the way.

Casio called captured images ‘Pages’ and the camera stored a maximum of 96 of them in its internal memory. The manual often refers to ‘memory pages’ and they could be write-protected if desired. In Playback mode, multiple thumbnails could be shown, and you could ‘zoom’ in in a primitive way on areas of the image.

The TFT display was backlit using a fluorescent light source, presumably a cold-cathode tube, which had a working life of about six years (at two hours per day). After that, you had to pay Casio to have a new tube put in, if the camera lasted that long and hadn’t become obsolete by then (which was highly likely in this supercharged market). Nor might the TFT have 100% integrity: out of its 61,380 pixels, up to half a dozen of them (0.01%) were allowed to be always-on or failed altogether, as stated in the manufacturer’s norm. A display brightness control was underneath the camera, near the tripod screw thread.

The camera’s spec was actually quite professional-sounding: the fixed-focus F2/ F8 lens had a ‘macro’ position and a shutter speed of 1/8th to 1/4,000th of a second, auto white balance, -2 to +2EV exposure adjustment and TTL centre weighted metering. A 10-second timer was included.

The spec sheet can still be seen at https://web.archive.org/web/19971114230210/http://www.casio.com/html/products/QV-10Adetail.html

I won’t describe every camera function in detail as the operating manual is still online at Casio.com, I guess for old time’s sake: https://support.casio.com/storage/en/manual/pdf/EN/001/QV10_EN.pdf

The swivel lens could take a selfie! [click to see]As another novelty, the lens could swivel 180 degrees – that’s right, it was also the first digital camera that took selfies! There was of course no built-in flash. I also have a rare lens adaptor kit for the Casio QV-10, the Raynox QV-1000 which contains a 1.5x telephoto and 0.65x wide angle lens. They clamped over the Casio lens using a plastic bracket. The whole thing was weighty and wobbly and the idea was quite laughable really, as it was very easy to knock it off or offset it, but it was the state of the art at the time.

The swivel lens could take a selfie! [click to see]As another novelty, the lens could swivel 180 degrees – that’s right, it was also the first digital camera that took selfies! There was of course no built-in flash. I also have a rare lens adaptor kit for the Casio QV-10, the Raynox QV-1000 which contains a 1.5x telephoto and 0.65x wide angle lens. They clamped over the Casio lens using a plastic bracket. The whole thing was weighty and wobbly and the idea was quite laughable really, as it was very easy to knock it off or offset it, but it was the state of the art at the time.

The rare Raynox QV-1000 conversion lens kit for the QV10 (click to see)

The rare Raynox QV-1000 conversion lens kit for the QV10 (click to see)

The heavy lens was retained on a primitive and wobbly plastic clamp [click to see]

The heavy lens was retained on a primitive and wobbly plastic clamp [click to see] The 1.5x telephoto and 0.6x wide angle lens kit by Raynox of Japan [click to see]

The 1.5x telephoto and 0.6x wide angle lens kit by Raynox of Japan [click to see]

Serial Killer

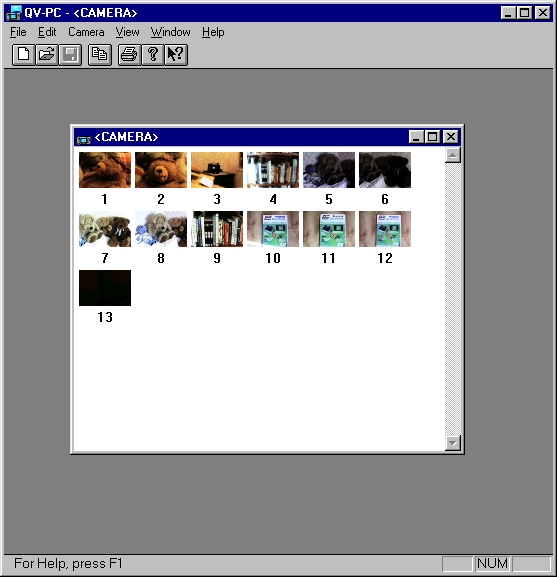

QV-PC Software running in Windows 98Using the separate QV-PC software application and Connection Kit, a QV-10 can be connected to a Windows (95/98) PC or a Macintosh. Remember that this was before the days of removable media, USB ports or flash card readers, etc., so here’s where the fun really began: a serial lead connected the camera to a COM (serial) port on a PC and it was vital that the camera’s power supply was uninterrupted during the image download/ upload process. Failure to maintain power could corrupt the camera’s memory! Apparently, if that happened the camera had to be sent back to Casio to have a factory reset, otherwise the camera was effectively ‘bricked’.

QV-PC Software running in Windows 98Using the separate QV-PC software application and Connection Kit, a QV-10 can be connected to a Windows (95/98) PC or a Macintosh. Remember that this was before the days of removable media, USB ports or flash card readers, etc., so here’s where the fun really began: a serial lead connected the camera to a COM (serial) port on a PC and it was vital that the camera’s power supply was uninterrupted during the image download/ upload process. Failure to maintain power could corrupt the camera’s memory! Apparently, if that happened the camera had to be sent back to Casio to have a factory reset, otherwise the camera was effectively ‘bricked’.

A revision, the QV-10A (in the UK anyway), permitted users to reset the camera themselves. An updated QV-11 followed, but the difference is a mystery as the main specs. were identical.

I happen to have a Windows 98 PC which I keep for old time’s sake – and I also have Casio’s QV-10 demo disk (CD ROM), which doesn’t run on a 64 bit PC so I made some screengrabs from the .AVI files into an animated gif. The colours are spotty but it gives you an idea.

Slides from Casio's QV-10 demo disk (Windows 98)

Slides from Casio's QV-10 demo disk (Windows 98)

Casio’s QV-PC Windows software is used to download images from the camera. A clunky but very fragile-looking serial lead hooks it to a COM port. Fetching images is a slow job, starting with the ‘Open Camera’ menu which downloads thumbnails. These are the key to everything and images can then be saved out as .cam .bmp or .tif format only. No JPGs here! The .cam format (Casio’s native file) is chosen by default. When saved out as a .bmp, the resolution can also be set, 320 x 240 (default) or extrapolated to 640 x 480.

Interestingly, when connected to the COM port the camera can be used to take a snapshot, webcam style. The software also flagged up that the camera battery was getting low, so there is a bit of bi-directional comms going on.

The software organises images thumbnails and albums, and is a reminder of how far we’ve come since the 1990s. It has no right-click and files had to be saved as 8.3 filenames. There was rudimentary drag and drop, with downloaded thumbnails being dragged onto an Album window: the software then fetched the image (again) and saved it as a .cam file.

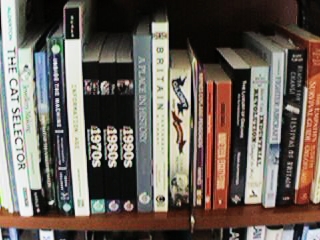

A sample photo is below, noting that I had to convert them from bitmaps to JPEGs for web use:

320 x 240 pixel native image

320 x 240 pixel native image 640 x 480 pixel (extrapolated) native image

640 x 480 pixel (extrapolated) native image

As shown above, native images were 320 x 240 px but bitmaps could be saved out as 640 x 480 px VGA.

Summary

The Casio QV-10 opened up the power of digital photography to the mainstream user and was the forerunner of things to come. I would invest in my first digital camera – a Sanyo VPC-G210 – in 1997, a decent-enough quality VGA camera costing £550 which radically transformed my workload later in the 1990s and enabled me to work much more efficiently. It’s something I’ll write about separately.

I hope you enjoyed this insight into digital photography of the era.

- Sanyo Digicam VPC-G210 - the start of something big

- Sanyo Digicam VPC-G210 - Exploring Multi-shot Movie Clips

Casio QV-10

Casio QV-10

Reader Comments