Interview Part 4: All The Muscle You Need!

Constructor's Rule - free with EE May 1980In previous parts of my potted history I explained how my interest in electronics evolved, and how I soon found myself working on my constructional projects and submitting magazine articles as a second job. The revenue was handy to a young lad and I built up a mini-conveyor belt of work, with a constant flow of ideas turning into reality as I breadboarded, experimented, soldered and refined projects as best I could, before laboriously writing them up in longhand and typing out everything manually.

Constructor's Rule - free with EE May 1980In previous parts of my potted history I explained how my interest in electronics evolved, and how I soon found myself working on my constructional projects and submitting magazine articles as a second job. The revenue was handy to a young lad and I built up a mini-conveyor belt of work, with a constant flow of ideas turning into reality as I breadboarded, experimented, soldered and refined projects as best I could, before laboriously writing them up in longhand and typing out everything manually.

Bench Power Supply

After my Ingenuity Unlimited variable power supply (LM305H/ LM395K based) was published in Practical Electronics way back in 1977 (see Part 2), someone from the Royal School of Veterinary Studies in Edinburgh wrote to me highlighting a new variable three-terminal regulator from National Semiconductor. It was called the LM317 and it fascinated me a lot. As it embraced everything I needed in a simple to use power supply, in 1979 I developed some ideas and revisited the thorny problem of having a decent bench PSU.

My new design had a pre-regulator to stop the rail floating too high, variable control using two LM317s as a voltage regulator and simple Low/ High current limiter. Taking a cue from an earlier effort which used an all-steel Bazelli case (that my Dad prepared for me), this one would be built in a “Norman” steel case with an aluminium chassis that I could punch and drill myself. I rushed to submit my final Bench Power Supply article in early 1979 as my parents were moving house imminently, leaving me with little time to put it all together on my Dad’s workbench in the old garage, and get the manuscript sent off.

EE March 1981 featuring the Bench Power Supply. No that wasn't me in the leotard. (Click to resize.)The Bench Power Supply eventually appeared in March ’81 Everyday Electronics (article and prototype notes - PDFs, open in new window), but only after they chewed over the article for more than a year; initially it was rejected as being too complex(!), until I explained the need for a pre-regulator and other features. I got an impression that the article was stuck on a heap at the publishers for a long time.

EE March 1981 featuring the Bench Power Supply. No that wasn't me in the leotard. (Click to resize.)The Bench Power Supply eventually appeared in March ’81 Everyday Electronics (article and prototype notes - PDFs, open in new window), but only after they chewed over the article for more than a year; initially it was rejected as being too complex(!), until I explained the need for a pre-regulator and other features. I got an impression that the article was stuck on a heap at the publishers for a long time.

My Bench Power Supply had multiple a.c. outlets on the rear and used a Chinese ALTAI copy of the Douglas MT79AT multi-tapped transformer (12,15,20,24,30V a.c.) that I’d got for my 20th birthday (for PSU Mk. I). The a.c. transformer was a trick I’d picked up from school, when we used multi-tapped a.c. transformers in Nuffield Physics: different a.c. voltages could be chosen by selecting suitable 4mm sockets (e.g. 12V and 15V terminals gave 3V a.c.) .

The PSU had a p.c.b. to make assembly idiot-proof, remembering that there were no home CAD systems so artwork was drafted using dry rub-down transfers onto clear film. I guesstimated how thick the copper tracks would have to be, but I’d figured out where the heavy d.c. current flowed on the board.

In the end, it was worth the wait and Everyday Electronics did me proud on the March 81 magazine cover, using a fabulously-photographed muscle-man (nothing like me!) holding the prototype aloft and captioned “PERFECT POWER FOR THE CONSTRUCTOR”. The article had a flash banner “All the muscle you need”. The March 81 issue is probably the magazine cover I remember the most, and the prototype lasted me a very long time afterwards. I think I scrapped it (can’t remember why) in the early 2000’s after 20 years of service! I also had I.C. Uniboards: 4 Mini Siren in the same issue – a simple but effective NE556 design, see Part 3 for details.

Bench PSU EE March 81: all that's left... (sniff)

Bench PSU EE March 81: all that's left... (sniff)

More small projects followed from my modest assembly line. Remember that I got paid the same page rate whether the project was simple or complex, so with an eye on commercial viability the projects were none too demanding but were hopefully appealing in terms of presentation and novelty.

These were very busy days for the electronics hobbyist, with lots to go at, several competing magazines jostling for attention and the hobby electronics readership was generally buoyant (these were pre-Internet, pre-iPod, pre-computer and pre- mobile phone days).

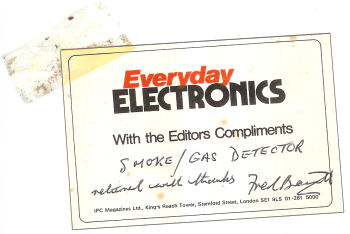

There was a perpetual paper trail of letters to-ing and fro-ing between myself and EE’s Editor Fred Bennett, but it’s inconceivable that such a volume of communications could be handled by letter post today. I’m still surprised that anything got published at all!

The October ’81 issue of EE carried “Ten Popular Designs” and three of them were mine. It also carried an advert from Vero celebrating 20 years of Veroboard, which dates the indispensable matrix board to September 1961. I cut out and used this issue’s £1 voucher to get a quid off a Veroblock!

I continued to develop my ideas for constructional projects, with the following appearing next:

Pressure Mat Trigger Alarm (Nov. ’81 EE article and prototype notes) – this latching alarm system used MOS op.amps to keep the quiescent current down. I’d built it for some trigger mats that Maplin were selling, big black polythene tin-foil sandwich things which had caught my eye when browsing their catalogue. I recall at the (day job) office how one of the girls marvelled at it, although her boyfriend had scoffed at the idea of writing an article and saying anyone could do that: she rebuked him because he hadn’t ‘done it’ and I had.

Siren Module (Jan ’82 EE article and prototype notes) –submitted back in July 1979 it took 2½ years to appear, a sign of the turbulent workflow that I had to contend with. It was a 555 self-contained driver that drove an external speaker.

In-Car PSU – this LM317-based (again!) box was for cigar-lighter use, offering 6, 7.5V or 9V d.c. It was painted Ford gold and was pretty much the last project I devised before my parents moved house, but astonishingly it took three years to make it into print in 1982. (See Part 3 for more details.)

I also noticed how computer-related projects were appearing more frequently in EE, reflecting the upsurge in home computing. Add-ons for the Sinclair ZX-81, Commodore PET and Radio Shack TRS-80 home computers were cropping up more frequently, adding yet another avenue of interest for the hobby electronics enthusiast to explore. Pages of computer code started to appear too. Hmmm... Meanwhile a small CMOS 555 project entitled “Power On Indicator” – a low-power flashing l.e.d. – was rejected.

Security Vari-Light (Dec ’82 EE article and notes) – this project was actually suggested by Fred Bennett and they wanted it (too) quickly. It was an example of pseudo-random number generation, a technique I’d lapped up from my favourite textbook The Art of Electronics. Unlike all my unsolicited projects that I submitted “on spec.”, a key point here was that Editor Fred Bennett asked me if I could design this project for them. I had great fun breadboarding it, and being self-taught, I figured the logic out for myself. It used 4070/ 4015 EXOR feedback to create a semi-predictable but very random-looking series of pulses.

EE December 1982 featuring the Security Vari-Light - (click to resize)The Security Vari-Light powered a mains lamp “randomly” into the night, to give the impression that a building was occupied and it had a 2-7 hour timer. In the end I had a ton of correspondence with EE because Editorial were unimpressed with the fact that it wasn’t fully randomised. EE became pretty obsessed with this project and went on and on about it, all by letter post of course.

EE December 1982 featuring the Security Vari-Light - (click to resize)The Security Vari-Light powered a mains lamp “randomly” into the night, to give the impression that a building was occupied and it had a 2-7 hour timer. In the end I had a ton of correspondence with EE because Editorial were unimpressed with the fact that it wasn’t fully randomised. EE became pretty obsessed with this project and went on and on about it, all by letter post of course.

They said that an “observant villain” may eventually notice the pattern, they called it “over-elaborate” and said it’s a pity that the switching was on a cyclical basis, and a better idea would have been to use random switching with a memory chip(!). This despite the fact that I had previously proposed a phasing/ heterodyning type of circuit that produced more-random-looking pulses still.

Whatever, I felt the pseudo-random project was fine and random in a predictable and realistic sort of way. Again I drafted the p.c.b. manually and I was pretty pleased with the results. It would still be do-able today, and exploring pseudo-randomness is a fascinating exercise in itself, especially if you can figure out the truth tables.

Hard on its heels followed the Opto Repeater (Jan ’83 EE). This Security Vari-Light add-on was completed in May 1982 and was intended to control a lamp in another room without the need for wires. It used the interesting 2N5777 photo transistor as a sensor and I built it into a sloping front console for some reason. You can read the original article and my prototype notes.

What a gas!

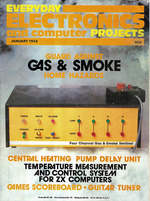

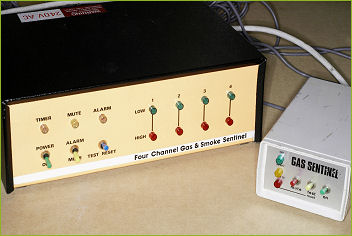

My Gas Sentinel in EE April 1980 (see Part 3) had proved very popular and several readers suggested a multi-channel version, so I had been experimenting with TGS gas sensors in the background. Actually, Everyday Electronics coined the moniker “Home Sentinel” in Issue 1 of EE, for a dusk-dawn relay.

Everyday Electronics & Computer Projects Jan. 84 (click to resize)A Four-Channel Gas and Smoke Alarm was submitted in Jan. 1982 but it took two years to appear in January 1984 (original article and prototype notes). EE umm’d and ahhh’d about the idea and they also wanted me to re-confirm in writing that it would detect smoke as well (it would, or rather the gases contained in the smoke).

Everyday Electronics & Computer Projects Jan. 84 (click to resize)A Four-Channel Gas and Smoke Alarm was submitted in Jan. 1982 but it took two years to appear in January 1984 (original article and prototype notes). EE umm’d and ahhh’d about the idea and they also wanted me to re-confirm in writing that it would detect smoke as well (it would, or rather the gases contained in the smoke).

I built it on stripboard, rightly or wrongly, as a p.c.b. was too much hassle. However, on the day itself EE went overboard to present the project, and they made the most of it. It’s one of the few that I can remember that had a whole page inside devoted to a studio-set photograph (page 17, Jan. 84 EE). I was thrilled because I still got paid for that extra page! This would also be the last ‘pink’ invoice signed off by Editor Fred Bennett, who was semi-retiring. My project also filled the cover, in colour.

Four Channel Gas & Smoke Alarm, pictured with the original Gas SentinelApart from anything, I was getting a bit disenchanted by the continual publishing delays and I seldom knew where I was. EE meantime, was printing more and more projects for home computing, especially accessories for the Sinclair ZX81 and Sinclair Spectrum, Acorn Atom and more besides. The April 1983 issue of Everyday Electronics was the final one of EE proper, and the May 1983 issue was re-titled as... Everyday Electronics and Computer Projects. The change of style wasn’t pre-announced in the previous month’s issue so maybe it was a quick re-think.

Four Channel Gas & Smoke Alarm, pictured with the original Gas SentinelApart from anything, I was getting a bit disenchanted by the continual publishing delays and I seldom knew where I was. EE meantime, was printing more and more projects for home computing, especially accessories for the Sinclair ZX81 and Sinclair Spectrum, Acorn Atom and more besides. The April 1983 issue of Everyday Electronics was the final one of EE proper, and the May 1983 issue was re-titled as... Everyday Electronics and Computer Projects. The change of style wasn’t pre-announced in the previous month’s issue so maybe it was a quick re-think.

The next several issues featured computing projects quite heavily, and I could almost feel my eyes glazing over at the thought of trying to get into all that kind of thing. Instead I was dedicated to hobby electronic projects, though I found the design and breadboarding side a bit of a chore and I probably enjoyed the construction side more than anything, finishing to a high standard with close attention to detail. Over-elaborate probably.

My files showed a change of typeface in my written correspondence: I’d invested in an electric typewriter in early 1983, a Silver Reed daisy wheel that had a brilliant keyboard but made a fearsome noise. (I recall the girl in WH Smiths: no we don’t sell typewriters made by Daisy Wheel, we only have Silver Reed.) Furthermore, it had a µ (micro) symbol which looked impressive in print, especially when typing Capacitor parts lists.

My files showed a change of typeface in my written correspondence: I’d invested in an electric typewriter in early 1983, a Silver Reed daisy wheel that had a brilliant keyboard but made a fearsome noise. (I recall the girl in WH Smiths: no we don’t sell typewriters made by Daisy Wheel, we only have Silver Reed.) Furthermore, it had a µ (micro) symbol which looked impressive in print, especially when typing Capacitor parts lists.

I felt the Security Vari-light and Opto Repeater projects didn’t seem to be so well appreciated despite being thoroughly worked out, and I felt a bit disheartened by that time, especially as the focus was switching to home computing.

Nevertheless my production line of projects continued and after coming home from work the house was often filled with the sound of my electric typewriter clattering away into the late evening.

Less is more

Small constructional projects rolled out but I had some more ambitious ideas bubbling away in the background. Anyway, the first manuscript in 1983 was Mains Monitor, a simple mains failure device using an opto-coupled alarm. It didn’t appear until Feb. 85 EE (article and notes), two years later! A Continuity Test Unit followed in March ’83, sporting two test plates made from touch switch pads sold by Maplin which I felt was ideal for testing fuses. It didn’t appear until July 85 EE (article and notes), well over two years later, and I started to realise that I could submit manuscripts far faster than the magazine had a capacity to publish them: or maybe the magazine was spoilt for choice and could pick and choose its raw material.

This added to my frustration and letters routinely passed to and fro between EE’s Editor Fred Bennett and me as I chased up my publication dates. I was passionate about my work and I have a whole sheaf of correspondence, some unbelievably two or three pages long, typed out very laboriously as I wrote to Editorial and they wrote back and prototypes went back and forth. Either I or my Mum posted letters or prototypes on the way home from work.

All change at EE

In June 83 I’d offered a Washer Fluid Monitor for cars which appeared a year later in August 84 EE (article and notes). Strangely though, in February ’84 a letter arrived from Practical Electronics magazine, asking for the prototype! IPC Magazines was moving Everyday Electronics from London to Poole in Dorset instead. Fred Bennett also wrote to say that both magazines would be produced by the same editorial team from March 1984 and Mike Kenward would edit both titles in Poole. Fred mentioned that he was retiring in 18 months’ time and would remain as Consultant Editor until then.

PE then wrote soon after enclosing proofs, galleys and artwork for the Washer Fluid Monitor article, which was a new one on me! I highlighted several corrections and posted them back.

Onwards to March 1984, and I offered EE a Drill Control Unit, a variable speed controller for low voltage p.c.b. drills, basically an LM317 with a footswitch and overload LED. It was accepted within the week but disappointingly did not appear until 18 months later, in August 1985 EE (article and notes). Incidentally, October 85 was the final issue of “Everyday Electronics and Computer Projects” as the November 85 issue embraced its Argus rival Electronics Monthly and was reborn yet again as “Everyday Electronics and Electronics Monthly” or EE&EM. The new office was also picking up loose ends from IPC in London, and projects that had been stuck in the works started to appear at last.

A bit of a failure...

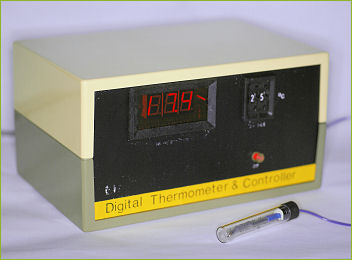

An AY-3-1270 based Digital Thermometer & Controller - the project never saw the light of day, but it did feel the heat.I continued to plough revenue back into developing new designs. For quite a long time I’d fancied building a temperature control project and after puzzling over data sheets I devised a Digital Thermometer and Controller (unpublished, but you can see it and read my prototype notes here) that I was especially proud of. It had a large LED display and two thumbwheel switches, with mains relay output. It was built into a large two-part verobox, had an all-in-one PCB and I was quite pleased with the engineering which had all been designed by hand. It had however taken a lot of time to develop and was quite expensive to put together. Much to my chagrin IPC Magazines rejected the article straight away, claiming the main i.c. (GI AY-3-1270, engrained on my mind) was obsolete!

An AY-3-1270 based Digital Thermometer & Controller - the project never saw the light of day, but it did feel the heat.I continued to plough revenue back into developing new designs. For quite a long time I’d fancied building a temperature control project and after puzzling over data sheets I devised a Digital Thermometer and Controller (unpublished, but you can see it and read my prototype notes here) that I was especially proud of. It had a large LED display and two thumbwheel switches, with mains relay output. It was built into a large two-part verobox, had an all-in-one PCB and I was quite pleased with the engineering which had all been designed by hand. It had however taken a lot of time to develop and was quite expensive to put together. Much to my chagrin IPC Magazines rejected the article straight away, claiming the main i.c. (GI AY-3-1270, engrained on my mind) was obsolete!

The chip was still widely advertised and I hadn’t reckoned that we might start to face component supply problems.

Undeterred, I broke the habit of a lifetime and offered the Digital Thermometer and Controller to Practical Wireless instead. PW too was published by IPC Magazines and (worryingly) they worked from the same office block in Poole.... I got a very polite and chatty letter back from Geoff Arnold, PW Editor, explaining that they were now only dedicated to radio projects so they couldn’t consider it.

Geoff added that they are very wary of specialised chips as they can go out of production overnight, and industry can snap up what’s left; or worse they have nasty characteristics as early TV game chips did – e.g. tanks that attached themselves to obstacles and the game needed rebooting. So I had to start thinking about component supply lines, which made me realise that designing something based around a special chip could end up in tears as it might be several years before the article could be published, and parts might be obsolete by then. Anyway, that was my only contact with Practical Wireless.

Electronics Monthly Jan. 85 nearly carried my temperature controller design... (click to resize)My final shot was to offer the Digital Thermometer and Controller to... Electronics Monthly instead, the main rival to EE. They wanted a fishtank controller and snapped it up. It was rapidly scheduled for publication during early ‘85. It was trailed as an Aquarium Thermostat on ‘Next month...’ in the December 1984 issue. I sent the prototype (nice engineering, they said)... and waited.... then EM cancelled the article! It seems those damned thermometer i.c.s had disappeared altogether. So IPC were right all along.

Electronics Monthly Jan. 85 nearly carried my temperature controller design... (click to resize)My final shot was to offer the Digital Thermometer and Controller to... Electronics Monthly instead, the main rival to EE. They wanted a fishtank controller and snapped it up. It was rapidly scheduled for publication during early ‘85. It was trailed as an Aquarium Thermostat on ‘Next month...’ in the December 1984 issue. I sent the prototype (nice engineering, they said)... and waited.... then EM cancelled the article! It seems those damned thermometer i.c.s had disappeared altogether. So IPC were right all along.

Electronics Monthly rushed to fill the void by publishing their own design for a “Fish Thermometer” in their January 1985 issue. It used an LM334Z and opto-coupled triac. The article included a plea for stocks of the AY-3-1270 so they could still run my ‘more up-market’ design as well! Editor Helen Armstrong was very nice about it and very sympathetic too. (I recall being sympathetic in return, when ETI etc. was absorbed by EPE and some good people lost their jobs. Being a freelancer is tough. There but for the grace of God etc.)

Hobby electronics was being influenced ever more by industry trends, component lead times and supply chains.

At the same time I noticed my Washer Fluid Monitor hadn’t appeared on cue either, and a proposal for a Decade Box resistor substitution box (unpublished - details here) was also rejected by PE/ EE’s new Editor. It didn’t seem like I was making any headway with the new publishing regime.

Things picked up a little in 1985, with the Mains Monitor (Feb. 85), Continuity Test Unit (July 85) and Drill Control Unit (August 85) appearing at last. EE celebrated this new-found burst of productivity by stopping my free monthly copy: if I wanted to read EE I’d have to subscribe like everyone else!

Competition was tough, page space was limited and the Publishers could afford to be picky. I still had some little constructional projects bubbling away just to keep my hand in, but with my regular job starting to suffer due to recession my life was full of twists and turns. In Part 5 I’ll explain how I wanted to build up a more streamlined and regular flow of work. Could I break into the big time?

Sunday, October 6, 2013 at 1:17PM

Sunday, October 6, 2013 at 1:17PM

Reader Comments